In June, Seoul-based venture capital firm FuturePlay sat down with addlight journal for a wide-ranging interview.

Without pulling punches, Partner and CEO Jung-hee Ryu and Specialist and Principal Oh-hyoung Kwon laid down their founding vision and motivation for the company, and how they plan to level the playing field between Asia, Israel, Silicon Valley, and beyond.

The self-described hyper-growth VCs—who focus their investments on early stage but next-wave industries like artificial intelligence, augmented reality, virtual reality, Neuro-technology, and robotics—spoke candidly about South Korea’s and Japan’s startup ecosystem.

Tantalizingly, they drew a stark contrast between the mindset of founders in Tel Aviv and Silicon Valley versus Seoul and Tokyo, and put forward their theory of why the former has out-competed the latter.

What can you tell us about FuturePlay and its activities?

We are early stage investors. We are engaged in co-building companies with entrepreneurs who have valuable technology and great teams, but need support to become great businesses. We make around 12 direct early stage, seed-to-pre-series rounds investments, and around five co-building partnerships, annually.

One way we support startups is through our TechUp Program. Through the program, we select a batch of five entrepreneurs that we invest in and mentor for a period of six months. We help them to incorporate the company, find co-founders, and creat an MVP (Minimum Viable Product) within six months, among other things.

If they make good progress, we make additional investments and link them to TIPS (Tech Incubator Program for Startups), a Korean R&D grants program for VCs and accelerators that they can invest in pre-equity startups. TIPS offers a “runway” that lasts a year or two.

To accelerate the TechUp Program, we started co-acceleration programs with large companies like Amorepacific, one of the largest cosmetics companies in Korea. This collaboration is similar to that between US-based incubator TechStars and retail giant Nike.

In our case, we work with Amorepacific, who have access to markets but need new technologies, and startups, who have the technology but need to access new markets. (Oh-hyoung Kwon)

What was the motivation for your visit to Tokyo?

We always want to act on the global scale. And there are many synergies between Japan and Korea (Taiwan included). We share similar cultural and technological backgrounds, and both countries have top-tier universities, companies, and technologies that are players on the global stage.

However, despite the talent pool that these countries have, we think they still need mentoring and support—be that investment or human resources and technological sourcing—especially when playing at the global level. That’s why we started FuturePlay, which is something we wish to extend to the Japan market.

In Korea, for instance, we have strong connections to research institutes and universities. We work with masters of science students there to help them develop their own companies. These are the types of collaboration that we can do in Japan, a country surrounded by awesome institutes and colleges but one that may need support to become a global player.

We are also seeking top-tier corporate venture capital (CVC) limited partnership investors in Japan and elsewhere, and in fact we already have secured such partners.

CVCs invest in us because we can act as an antenna or thermometer that measures the state of play in the early stage startup market. We believe Japanese CVCs also have a need and desire to tap into that market. (Jung-hee Ryu)

Would you like to add to that?

Yes, we’re really trying to build an ecosystem around us. We’ve tested and proved our hypothesis on how a tech company can become a global company.

We were able to do that with Olaworks Inc (a company that created first-generation artificial intelligence products) because the company was not based purely on the domestic market or culture, as is sometimes the case with startup companies in Japan.

The easy thing for me to have done is to create another company, as I already have experience and success doing that. In that case, others would look at me and say, ‘Oh, he’s an exceptional guy. I can’t do that.’ But what I decided to do instead is to support and encourage others to become founders, and to say to themselves, ‘I can do that.’

(Jung-hee Ryu)

So we believe we can replicate that experience in Japan, Taiwan, and among Asian American-founded companies in the United States. But to do that, we need to bring even more powerful players and partners into our orbit. (Oh-hyoung Kwon)

What can you tell us about yourself, Jung-hee, as CEO of FuturePlay?

I’m a kind of inventor. I have always been interested in making new devices or interfaces to serve others. I created my first startup when I was a Ph.D candidate at the Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology (KAIST).

I spent six years at the company, where I was the CTO. But that startup became a kind of “zombie company,” meaning we spent about the same amount of cash as we made. As a result, we didn’t manage any M&A or make an IPO. Soon after in 2006, I decided to leave to create artificial intelligence company Olaworks, where I became CEO. We were acquired by Intel Capital in 2012.

At Olaworks, we considered ourselves an A.I. company, even though that word was not used often when we were founded—computer vision, facial recognition, object recognition, and augmented reality were more common terms for the technologies and engines that we provided. Some of our clients were Samsung, LG Electronics, and so on in the Asian market.

Interestingly, there were no iPhones when we started in 2006, but we believed that smartphones were just around the corner, that the camera they would contain would be “smart cameras,” and image recognition would play a big part in them.

So we focused on facial and object recognition software. We were one of the first companies to apply this kind of technology in smartphones and the kind of user interfaces common today.

Joining Intel had a profound influence on you. Please explain.

I spent two years working at Intel in Seoul where, as CEO of Olaworks after we were acquired, I was involved in business application strategy. I also experienced Intel’s M&A strategies, and noticed that a lot of their acquisitions were of Israel-based startups.

We want to transform Asian engineers and Asian entrepreneurs into global players.

(Jung-hee Ryu)

While many of these startups were small, with around five members or so, their valuations were usually quite high compared to similar companies in Asia—including Olaworks, which was acquired when we had around 60 staff and the business was doing well.

So I wanted to know why there was such a difference in valuation between Israeli and Asian startups. Interestingly, after our acquisition by Intel, there have been very few acquisitions of Korean startups by big, Silicon Valley-based companies like Apple or Google.

So I decided to build VC platforms to connect the United States and Asia using the Israeli approach: In our case, this means being a global player by having headquarters in the United States and branches in Asia while, at the same time, improving the company’s valuation. (Jung-hee Ryu)

Are there differences between Israeli and Asian startup founders?

Yes, and they can be summarized in one word: khutspa, which is Yiddish for “audacity”—or having the guts to take bold actions. When I was at Intel, for example, I had a lot of Israeli colleagues based in Haifa, Israel, with whom I had many email exchanges or conference calls.

I noticed that they were very bold when they asked me to do something. But when I checked their level in the company hierarchy, I noticed they were of lower rank than I was—and yet here they were giving me orders. My response, as an Asian, was to write a polite email questioning whether it was their place to order me around.

The reply was something like, “Well, you don’t have to do it,” which was quite direct, and typical of the Israeli way. If they want something, they ask for it. If they have great technology that they wish to sell to a large company like Intel, they approach them directly. I don’t think Asian companies, including Japanese ones, are that direct.

I also think Israelis benefit from the experience of military service; they are used to being in battle and fighting for survival. They know how to stay hungry, as Steve Jobs would have said. They also tend to be practical and, even in university, they are not too stuck on theory. And they know they have to innovate and to find new technological solutions via cross-disciplinary collaboration in order to guarantee survival.

In Korea and Japan, things are a little different. People here tend to stay within their area of expertise. Israel’s genius is in knowing when to mix new fields to create new innovations, in addition to being great communicators.

Another theory about Israel’s startup success says: “They never had a Samsung.” That is, they have not had a long industrial heritage. So when some years ago a number of engineers from the Soviet Union emigrated to Israel, there were no companies there of the size of Samsung that could suck them up.

Many of these highly talented people—who were graduates with Ph.Ds and MSc—had to create jobs for themselves. Japan and Korea, on the other hand, have for some decades a lot of large companies that sucked up a lot of the entrepreneurial talent and dominated the talent pool.

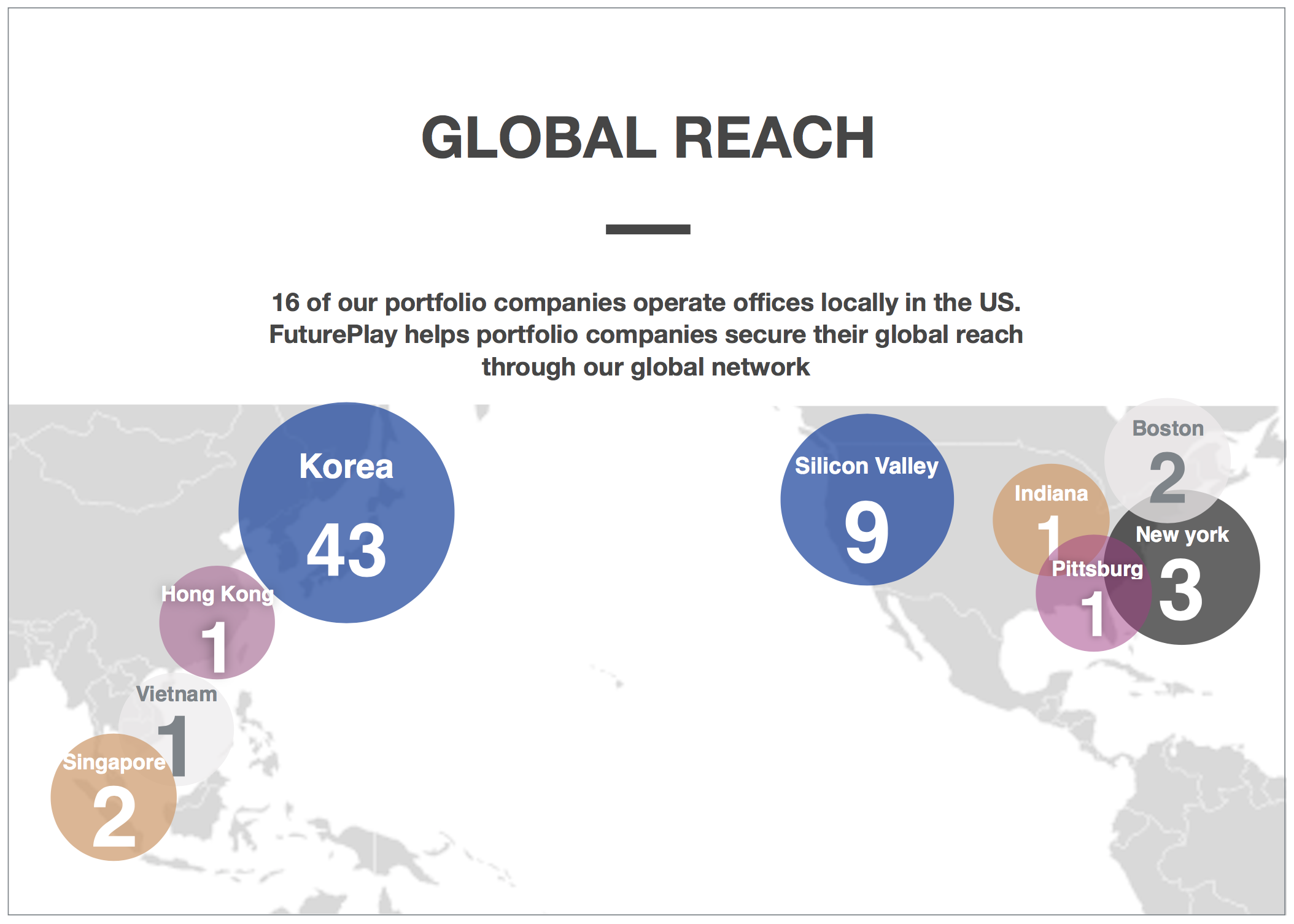

FuturePlay has invested in some 54 companies globally, of which one-in-three are in the United States, and the rest mainly in Korea and other parts of Asia.

(Oh-hyoung Kwon)

To found a startup in Korea, for example, means going up against a Samsung, LG, SK (SK Group), or Hyundai—and within a relatively small market, which can be hard work. That is not the same in Israel. And the last thing is, English is spoken widely in Israel, which is an advantage. (Jung-hee Ryu)

Are there any advantages that South Korea has over Japan in the startup world?

I think Koreans are more aggressive than Japanese. As you know, we recently changed our president by exercising citizen power. This is typical of Korea, especially among the younger generations—if we don’t like something, we can change it.

So you will find young people looking to make money outside of the big companies, or if they don’t make a lot of money, at least they want to enjoy their lives. They are also more willing than the “Samsung generation”—or their parents’ generation—to make a bet on success and failure. In Japan, I think people are more willing than we are to follow the status quo. (Jung-hee Ryu)

Can you add to that, Oh?

Yes, Korea, like Israel but unlike Japan, has a small market. So Korean startup founders always think about going global. They never really think about their own market; for them, the goal is the United States or China, in addition to Korea itself. (Oh-hyoung Kwon)

What can you tell us about South Korea’s startup hotspots?

We have four hot cities. The first is Seoul, with its center in the Gangnam area. This is a weird place where cultural kids mix with engineer types, so there are a lot of K-pop styles and startups in the area. And with movements like K-beauty, you have a blend of tech- and culture-savvy startups taking off.

Actually, one of the core competencies of Korean startups is their ability to mix culture with technology. We at FuturePlay, for example, announced our core program collaboration with SM Entertainment, a leading K-pop company.

Gyeonggi and Pangyo in Seoul are also hot spots for startups. If you think of Gangnam as San Francisco’s Downtown, Pangyo is something like Palo Alto. You can find large, maturing companies around the Pangyo area, while smaller, startup types are found in Gangnam.

The other city is Daejeon, in the central part of the country. It is known as a tech city, with lots of engineering talent, as well as many universities and research institutes like KAIST. It is like “the Boston of Korea.” There are a lot of deep tech startups emerging from the city.

More recently, Pusan has emerged as a city on the rise. It is something like Osaka—or Fukuoka—in Japan. Like the people in Osaka, those in Pusan are very straightforward. They have had a long manufacturing history, and their latest generation of owners have often had a US-based education, which has inspired them to create their own innovation ecosystem. The VCs there are aggressively investing in local talent.

And there is Jeju Island, which is like “the Hawaii of Korea.” Jeju is popular with the country’s youngest generations. Thanks to tax incentives on the island, many large companies—like Internet firm Kakao Corporation and gaming company Nexon Co. Ltd.—have relocated there. Nexon, interestingly, is listed on the Tokyo Stock Exchange, even though they are headquartered in Jeju. (Jung-hee Ryu)

RELATED LINKS:

You can find out more about FuturePlay here.

For media (in Korean) about the startup ecosystem in South Korea, see Platum.

For more on the company Jung-hee Ryu sold to Intel, see: Olaworks, a computer vision development company that was based in Seoul.